The sound I saw…

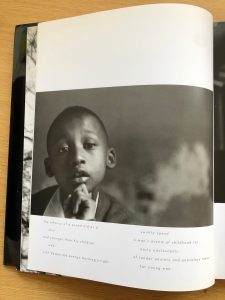

Conceived, designed, written and made by hand by master photographer Roy Decarava, The Sound I Saw brings words and images together brilliantly to tell its story. As Roy says in the introduction, “This is a book about people, about jazz, and about things… It represents pictures and words from one head and one heart.”

What a head; what a heart. And what a hand and eye:

Through big arresting black & white images, Roy weaves words in carefully crafted lines, rather than unthinking blocks of text. Lines are broken here, indented there, always in service of the story Roy wants to tell. It’s what the great information artist Edward Tufte calls content-responsive typography in his latest book Seeing With Fresh Eyes. In this way, Roy amplifies the meaning and melody running through The Sound I Saw.

Inspired by Roy and Edward and in lieu of a new year’s resolution, here’s a new year’s tip:

write with your eyes and ears.